Why Apprenticeships Are Fewer in High Skill Sectors

Apprenticeship programs bring about substantial overall benefits to apprentices, firms, and aggregate production, but their design should take into careful consideration the training costs faced by firms with different features (namely workers' skill requirements) if they want to avoid market distortions.

In an article forthcoming in Econometrica, Miguel Espinosa, Assistant Professor at Bocconi Department of Management and Technology, found evidence of heterogenous firm responses to apprenticeship regulation in Colombia with coauthors Santiago Caicedo (Clemson University) and Arthur Seibold (University of Mannheim).

Infographics by Weiwei Chen

The authors analyze a large-scale change in Colombian apprenticeship regulation introduced in 2003.

In the early 2000s, Colombia experienced high levels of informal employment and youth unemployment: The informality rate in 2002 was 62% overall, rising to 70% that of young workers aged 18 to 24 years, and the youth unemployment rate was above 30%. Therefore, a market reform was introduced in 2003 to expand apprentice training by setting apprentice quotas depending on the number of full-time workers in a firm and lowering the minimum wage of apprentices. Firms also must pay extra fees if they do not hire the minimum required apprentices.

The reform turned out to be successful in increasing the number of apprentices to more than fifteen times the pre-reform levels, allowing many more young individuals to receive training in the formal labor market. However, strong differences in response across sectors and firm size were recorded.

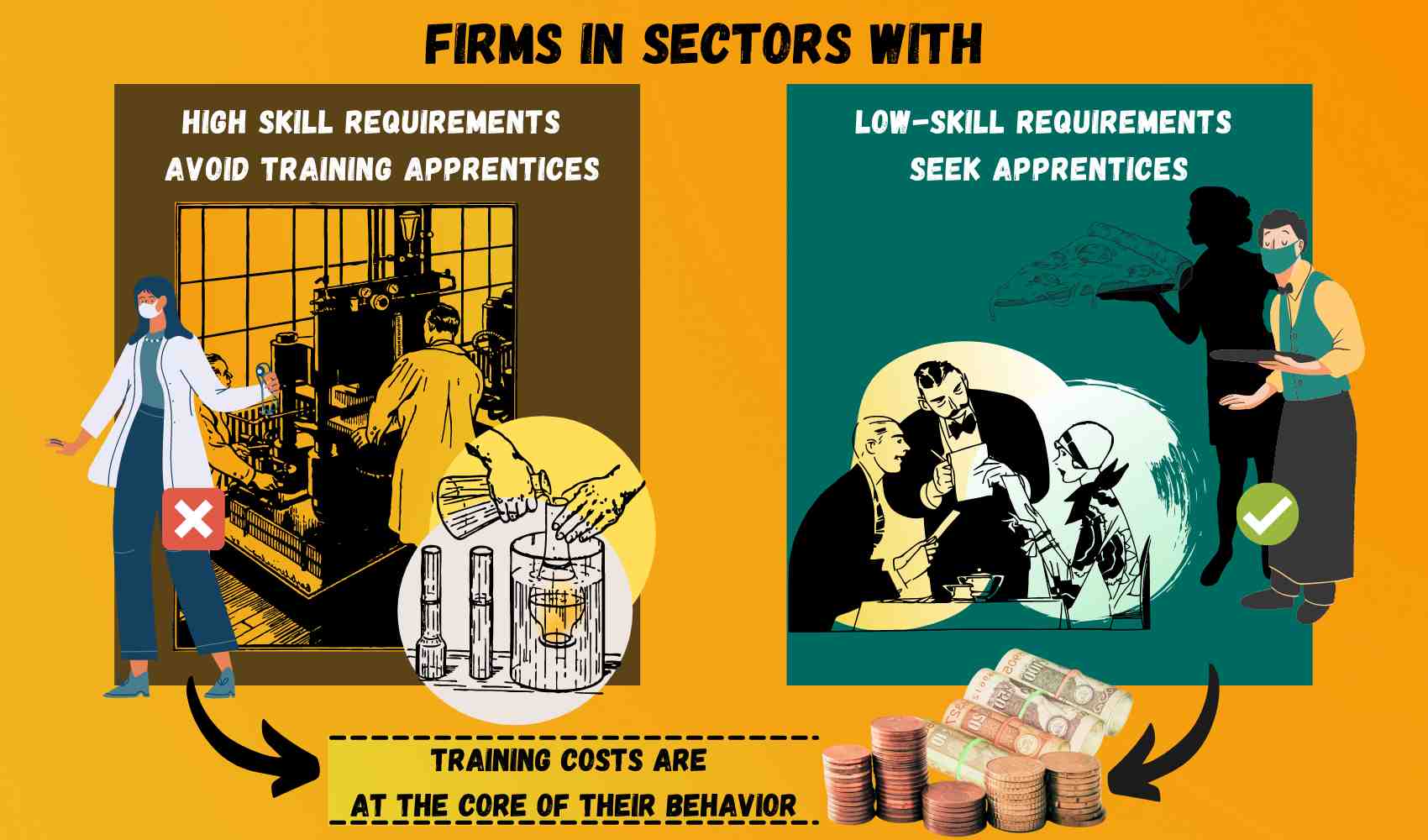

Firms in high-skill sectors reduced the number of regular workers to avoid the higher minimum apprentice quota that would apply above certain thresholds. Low-skill sector firms, on the other hand, increased the number of workers in order to increase their maximum apprentice quota, so that they could train and employ more low-cost apprentices. Often, high-skill sector firms chose to pay the fee rather than training apprentices.

The scholars found that firms in high-skill sectors face large costs to train apprentices, and this limits their willingness to do so. While the overall number of apprentices increased sharply, most training occurred in low-skill sector firms.

"Even if the overall benefit is clear, the apprenticeship regulation also creates losers," Professor Espinosa notes. "The incumbent, trained workers, may find it harder to find a job since they can be easily replaced by less expensive apprentices."

Given the large training costs many firms face, policy interventions such as training subsidies would have to provide sizeable incentives to firms to achieve a broad increase in training. "Policies that take into account heterogeneity in training costs, such as sector-specific apprentice minimum wages," Prof. Espinosa concludes, "can deliver additional benefits."

Santiago Caicedo, Miguel Espinosa, Arthur Seibold, "Unwilling to Train? Firm Responses to the Colombian Apprenticeship Regulation." Econometrica, Forthcoming Papers.