Ukraine, how the economy has kept running

November 24 marks nine months since the Russian invasion of Ukraine began. Despite the expectation of the Kremlin – and many international analysts – Ukraine did not fall within days. It repelled Russia's advance on the capital Kyiv, turned the tide on the battlefields and has now retaken half of territory captured in Russia's initial push. Ukraine's military now has initiative and momentum on the battlefield.

But the human cost of this resistance has been enormous. Tens of thousands of Ukrainian soldiers and civilians have lost their lives. The recent UN Human Rights report confirmed the death of 6,595 civilians and warned that there are many more likely to come. One-third of the 44 million population has been displaced: 6.5 million within Ukraine and almost 8 million as refugees in other European countries.

Having failed to complete its mission on the battlefield, Russian forces have resorted to terrorising the civilian population with missiles and drone attacks. These have resulted in many civilian casualties and severe damage to critical infrastructure.

The blockade of Black Sea ports is preventing vital exports and starving the Ukrainian economy of the foreign currency it needs to buy critical imports. This, and the fact that the government has been forced to divert public money for military use, has put tremendous pressure on the economy.

So how has the Ukrainian economy adapted to the new wartime reality?

After losing a relatively modest 4% of GDP to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the Ukrainian economy grew at a healthy 3.2% in 2021 and was expected to grow at the same pace in 2022. The sudden Russian invasion upset this forecast. The initial stage of the invasion hit the capital Kyiv and ten regions, which jointly account for 55% of pre-war GDP.

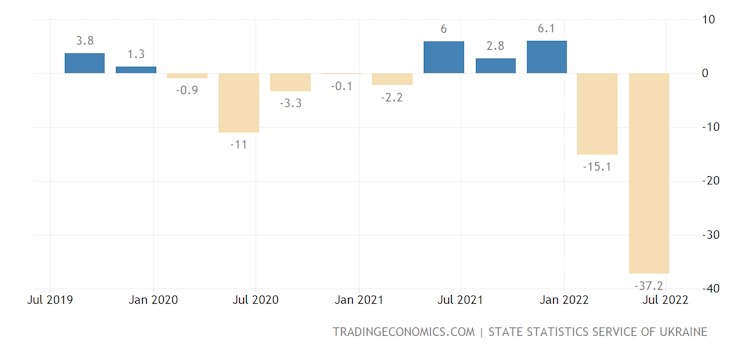

Ukraine's GDP shrank by 15.1% in the first quarter of 2022 – the year-on-year decline recorded in March 2022 was a massive 45%. In the second quarter, GDP fell by a staggering 37.2%.

Today, the fighting continues in the regions that account for less than 15% of pre-war GDP. But even so, the World Bank estimates that the Ukrainian economy will shrink by one-third in 2022, a far higher number than the typical threshold of 15% that economists us to start referring to a severe economic recession as an economic disaster.

Ukraine's economy was recovering, until Russia invaded. State Statistics Service of Ukraine

Ukraine's economy was recovering, until Russia invaded. State Statistics Service of Ukraine

What makes the economic consequences of the war even more dramatic is that the aggregate numbers above have unequal distribution across the country and socioeconomic groups. One way to illustrate this is to look at the extreme poverty rate, defined here as living on less than US$5.5 (£4.54) per person per day.

Before the war, only 2.5% of Ukrainians lived in extreme poverty, similar to Italy and Spain. The war abruptly changed this. The World Bank estimates that the number of Ukrainians in extreme poverty will likely increase tenfold in 2022 and will continue to grow in 2023. The poverty rates will be higher still in the regions closer to the front line, due to shortages.

This will accelerate the inflation rate and erode purchasing power. Government support for the low and middle-income parts of the population is crucial in this situation.

Despite the constant shelling risk, the massive destruction of buildings and equipment, and the loss of workers due to relocation, most Ukrainian firms continue operations. How do they do it? Businesses that are more mobile have relocated to safer parts of the country, leading to bursts of regional growth. For example, three central and western Ukrainian regions which have been untouched by the war grew by more than 8% in March 2022 compared to a year before.

The IT sector, with minimal requirement of capital input, barely stopped operating. Sectors far away from the active battlefields, such as retail, almost returned to their pre-war activity level by September.

Sectors disproportionately represented in the heavy fighting regions or with high capital intensity – such as metal production – have had to scale down substantially. Metinvest, the biggest steel producer in Ukraine, lost two plants in Mariupol but continues operations at other plants near Zaporizhzhia in southern Ukraine and Kamianske in the centre of the country, with the overall output reduced by 50-70%.

The grain deal negotiated in July with the help of the UN and recently extended by another 120 days has allowed partial grain exports – which has been beneficial to the agricultural economy. The export revenues may even be enough to plant for the next season. All these margins of adjustments helped the economy stabilise in early autumn.

But since the beginning of October, Russia has intensified attacks on critical infrastructure, destroying an estimated 40% of the Ukrainian power grid. As I write there is news of another Russian attack. Vitali Klitschko, the mayor of Kyiv, reports that 80% of the capital has no electricity or water supply. The government responded by rationing electricity, allowing key sectors – such as health care and public transportation – to receive enough or at least some power.

Some businesses are able to partially adjust to temporary power outages, for example dentists – who can set their visits according to the electricity rationing schedule. Similarly, some producers – such as the KMZ factory in Poltava, a manufacturer of grain handling equipment – run their production at night. Coffee shops have switched from selling electricity-intensive espresso to simpler filter coffee. Those who can afford it stock up on electric generators.

Anticipating electricity, water and heating supply disruptions, the government prepared thousands of shelters, "points of invincibility" where Ukrainians can receive all essential services free of charge 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

While Ukrainians and Ukrainian businesses constantly adapt, Ukraine needs to repair damaged civilian infrastructure to allow people to earn a living and to save the most vulnerable Ukrainians from the consequences of extreme poverty. But it also needs to supply the military to enable it to continue fighting.

Speaking at meetings of the World Bank and IMF in October the president, Volodymyr Zelensky, announced that Ukraine required US$38 billion to cover the estimated budget deficit in 2023 and further $17 billion to start rebuilding infrastructure that has been damaged or destroyed.

If Ukraine receives this support it should enable the country to avoid economic collapse and help it to continue fighting.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.