From Punch Cards to ChatGPT, the Adventure of a Bayesian at Bocconi

In late September 1976, fresh out of high school, Piero Veronese had not yet decided what to do from then on. "A friend of mine then told me about DES (Economic and Social Disciplines), a new course in its third year of existence, which was said to combine mathematics, which I loved, and social engagement. So, I decided to go to Bocconi." And he has hardly left since, witnessing 45 years of a journey that has transformed the university and the society around it beyond recognition.

This afternoon, the Department of Decision Sciences will be honoring him with Advances in Bayesian Statistics, an International Workshop in Honor of Piero Veronese, an opportunity to exchange reflections on some past and future aspects of Bayesian inference.

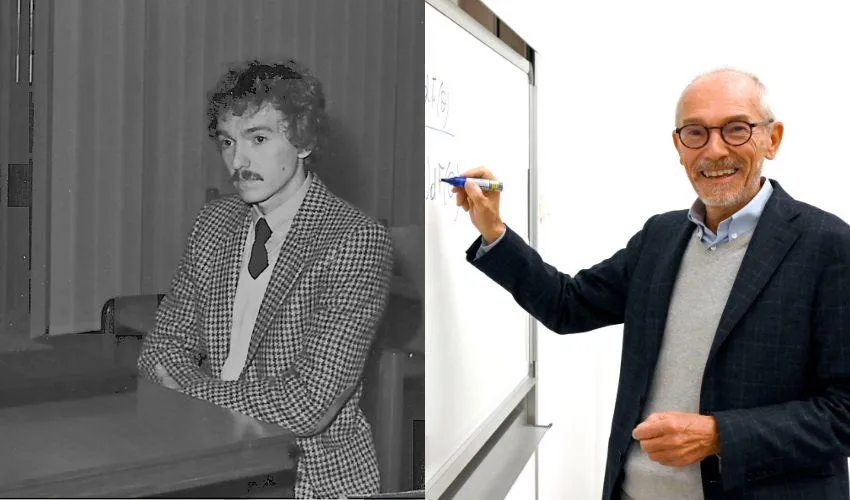

|

| Veronese on Graduation Day |

In 35 years of teaching, Professor Veronese, now considered an authority in the field of Bayesian Statistics, on top of having taught in Master and PhD programs, reckons that he has taught basic Statistics to more than 10,000 students, "because I believe contact with young people just beginning university is fundamental, in order to give them a comprehensive perspective on statistics, stimulating their interests and curiosity." Students in the late 1980s may remember him by the nickname Boniek, which they thought to be unbeknownst to him, because of his strong resemblance to the Juventus and Roma footballer.

What prof. Veronese knew as a student was a Bocconi smaller and more Italian than today. "There were a dozen full professors, including Francesco Brambilla, our Professor of Statistics, and there was practically no trace of foreign students or faculty. Although the University opened at 9am, Brambilla nonetheless started classes at 8.30, letting us in through a backdoor. The lecturers who got me interested in Statistics, however, were Donato Michele Cifarelli and Eugenio Regazzini, pioneering scholars of the Bayesian inferential approach, which was beginning to advance in those years, in contrast to the more traditional frequentist approach. Cifarelli, in particular, had gathered at the then Institute of Quantitative Methods (IMQ) a group of DES students who were more interested in Statistics than in Economics, and I began to spend my days between the library and the institute, rather than going home at the end of classes, as I had done until then. In that group of young people, now all at Italian and foreign universities, were also Sonia Petrone and Francesco Corielli who are still at Bocconi."

The debate between frequentists and Bayesians in those years was fierce, and Bocconi's IMQ, along with similar teams at the universities of Trieste and Rome, took the Bayesian side. "We considered ourselves as a bit like Guelphs and Ghibellines, and the enthusiasm was sky-high," said Prof. Veronese

In simple terms, the difference between the two approaches stems from their different understanding of the notion of probability. While a frequentist always interprets probability as the relative frequency of success of an event that can be repeated an infinite number of times, for a Bayesian probability is the degree of confidence that anyone attributes to the occurrence of any event, and different subjects may, therefore, give different probabilities to the same event depending on their personal knowledge of the phenomenon in question. Bayesian inference actually establishes the rules by which these probabilities are to be updated when new data become available. To understand how natural this approach is, consider a physician who has to make a diagnosis for one of his patients whom he has prescribed a clinical exam. He will obviously not rely just on the exam results but will also take into account all his experience in similar cases. "Today, however, the conflict has subsided," Prof. Veronese said, "and we tend to use the approach that best fits the problem to be solved."

After graduation and a PhD (run by a consortium of universities that included Bocconi), Veronese returned in 1987 to IMQ, "which was working in a kind of limbo," he said. "The rest of the university basically saw us as service providers, that is, providers of the Math and Statistics courses as building blocks to teaching economics and management. But we saw ourselves as a pure research center, and our point of reference and comparison was the international scientific debate, with the relevant journals, fifteen years before the revolution that would later involve Bocconi as a whole." Veronese's first publication in a top international journal, Biometrika, dates back to 1989 and was co-authored by Guido Consonni, thus consolidating a collaboration that would last for many years.

The old IMQ and then the Department of Decision Sciences (of which Prof. Veronese was director between 2008 and 2013, ed.) also served as an incubator for disciplines that were to gain a lot of importance at Bocconi. "Econometrics, Demography, Quantitative Finance, within the University, started here," said Prof. Veronese, "as did the early core of computer science. As a matter of fact, some machine learning techniques are based precisely on Bayesian principles."

The rise of computer science has been truly spectacular. If the topic du jour today is ChatGPT, when Veronese was a student the closest thing to computer science at the university was a course in automatic computing. "Of course," he recalls, "we had to use a computer center with punch card machines. At the exam I had to present a pack of cards as thick as a notebook to program a system capable of nothing less than... putting the cinemas of Milan in alphabetical order!"

|

| In the Tassili |

All these years Veronese has also walked another kind of path, made of steps in the mountains and deserts in the company of a small circle of friends, mostly those from his high school days. The trip of a lifetime, the one he made in 2008 in the Tassili n'Ajjer, a Sahara Desert plateau in southeastern Algeria. "We were doing 30 kilometers a day, forgetting all the worries of Western life," he said, "among 10,000-year-old cave paintings and pristine landscapes. And now we are planning a tour of Annapurna."

The latest change he witnessed, however, was not spontaneous, and it was not just at Bocconi. "The COVID years were really tough," he said. "After that experience, expectations and feelings experienced by kids have changed. Technology helped soften the impact and new and interesting methodologies developed, but something has really changed forever."