Informality in Small State Governments: A Double Edged Sword

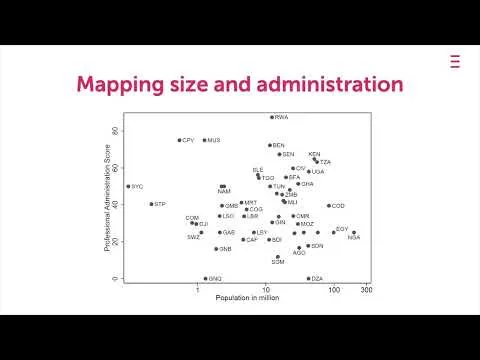

Not all countries are born equal in population size. With its 1.4bln people, China is more than 1,000,000 times larger than Vatican City and 100,000 times larger than the small Pacific island states of Nauru and Tuvalu. The United States is about 13 times larger than Australia. In her recent book Country Size and Public Administration (Cambridge Elements in Public and Nonprofit Administration) Marlene Jugl (Bocconi University Department of Social and Political Sciences) highlights the important, and yet understudied implications of size for public administration. Large states with larger administrations benefit from specialization but are prone to coordination problems, whereas small states experience advantages and disadvantages linked to multifunctionalism and informal practices. Midsize countries may achieve economies of scale while avoiding diseconomies of excessive size, which potentially allows for highest performance. Using descriptive and causal statistical analyses of worldwide indicators and a qualitative comparison of three countries, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Germany, Jugl demonstrates the various ways in which size matters for public administrations around the world. Bocconi Knowledge, courtesy of the author, publishes an excerpt from the book.

It is important to note that administrative practices in small states are not simply a mirror image of practices in larger states. They are not defined exclusively by the lack of size, specialization, and Weberian features. Rather, the meta context of small states and societies produces additional characteristics that influence administrative practices: the role of proximity, personal ties, and informality. The small size of the administration and of single administrative organizations allows many bureaucrats to know each other personally and maintain personal relationships. In addition, small country size affects administrations through the size of the society and the resulting dense social relations: the key concept is again "polyvalence," but here, it is used to highlight the fact that individual public servants occupy several, overlapping roles in the private and professional realm. And, because the private realm is as restricted numerically as the realm of public administration, it is very likely that the same individuals interact in both worlds. Dense social networks with a prevalence of kin and personal ties permeate small societies and overlap with professional roles. Anthropologists Gingrich and Hannerz, for example, suggest that small units display "role combinations that might seem surprising to an observer from a country of another size," a situation "where the same people show up in many roles, knowing each other and perhaps knowing too much about each other."

It is common in small states that public employees know their colleagues not only from collaboration at work but also through personal contacts, which qualify their work interactions. If a small state has only one university, it is most likely that top bureaucrats knew each other as students and share a similar educational experience. In theoretical terms, these features of small societies lead to more similar backgrounds and more personalized relations and interactions within small state administrations. Several case studies have testified to the empirical importance of kin ties and personal relations for small state politics, which is closely intertwined with public administration. Although empirical studies of these phenomena in public administration are largely lacking, it is plausible to assume that they also dominate there.

The literature is quite clear, however, that this particular social environment promotes informal administrative practices: bureaucrats in small states often report that they simply pick up the phone and directly call their colleagues or politicians who are responsible for a certain topic, thus bypassing formal hierarchies. This common practice makes coordination within the public sector quicker and more flexible, but it blurs lines of responsibility and accountability. Proximity and personal relations can also plausibly enhance trust within and between administrative organizations, which can partly substitute formal monitoring institutions, reduce communication and administrative costs, and boost effectiveness. This informal control could, however, be perverted and lead to a lack of effective monitoring or to the abovementioned capture and clientelism.

Looking beyond the administrative system, the smallness of society and the limited number of public actors allow politicians and bureaucrats to be in close contact with each other and with citizens. The lack of professionalism in the administration explained previously, together with the typical nearness of politicians and bureaucrats due to common educational backgrounds or personal relations, may encourage forms of nepotism or clientelism and hinder the effective fulfilling of administrative functions. Moreover, informality also dominates public employees' interactions with citizens. Sutton portrayed this in a very positive light: "senior administrative and political office holders have more direct contact with the man in the street, and accordingly there is less of the aloofness traditionally associated with a bureaucracy." Yet we should be careful in our analysis: if a bureaucrat personally knows a citizen requesting a public service, which is more likely in small societies, it becomes more difficult to follow formal, Weberian rules and ensure neutrality and impersonal treatment. Depending on whether close relations among bureaucrats and between bureaucrats and citizens are friendly or hostile, they might either increase levels of trust, facilitate and accelerate administrative procedures, or, on the contrary, block them and inhibit the professional functioning of the administration.

This material has been published in https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009122887. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution or re-use. © Marlene Jugl.

Elements in Public and Nonprofit Administration: Country Size and Public Administration