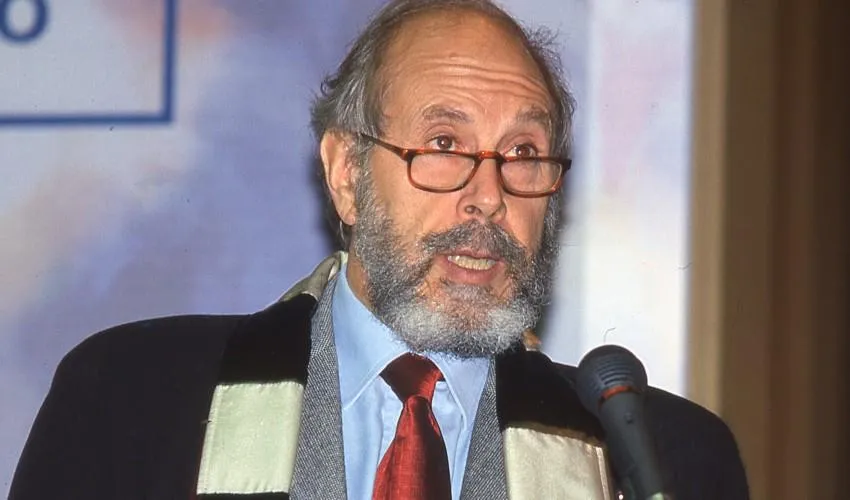

Giorgio Sacerdoti, a Jurist Who Climbs Mountains

To say this today seems almost an absurdity, but there was a lengthy period during which legal studies at Bocconi were marginal, little more than a complement to economic studies. This was despite the prestige of the Sraffa Institute as a center of comparative law and the fact that Bocconi had had more than one jurist rector, including Angelo Sraffa himself in the 1930s. It was not until the mid-1990s that a law and economics degree program, CLELI, was launched, closely followed by a law program in the early 2000s. Hence the gradual strengthening of the group of law professors, including Giorgio Sacerdoti, first an adjunct professor (since 1986) and then a Full Professor of international law since 1994. In honor of his 80th birthday, many gathered at Bocconi in March for an event that included speeches by Rector Francesco Billari, Senators Mario Monti and Liliana Segre, and fellow academics Piergaetano Marchetti, Nerina Boschiero and Gadi Luzzatto Voghera.

Among the first Italian jurists to sense how important European law would become, Sacerdoti took on an international profile from the very beginning, not only in his studies, starting with a Master's degree in comparative law at Columbia University, immediately after his Italian degree in 1967. In parallel with his academic commitment, he was selected to hold important positions within international organizations, both as an Italian expert and representing the European Union.

In 1995 he became vice-chairman of the OECD Committee on Bribery in International Trade and then chairman of the Drafting Committee of the 1997 OECD Anti-Corruption Convention. From 2001 until 2009, he was a member of the highest international trade tribunal, the Appellate Body of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in Geneva, which he chaired in 2006-2007. In this capacity he was called upon to decide key disputes between countries on trade, environment and development issues. Subsequently, and to this day, he has often been asked to arbitrate international disputes between foreign investors and governments at the World Bank's arbitration center in Washington. Some of his decisions have become case law, such as in the first case against China at the WTO, and about the treatment of foreign investors in Argentina during the financial crisis of the early 2000s.

These international commitments and academic endeavors reinforced each other: in 1990 he created the doctoral program in International Law and Economics at Bocconi – at the time the first of its kind in Italy – set up from the beginning with a strong interdisciplinary vocation. In that doctorate, not surprisingly, more than 100 students, both Italian and international, were educated who then went on to have careers in Italy and abroad in fields including academics, research, international development, diplomacy and law. "I recently met a student of mine from those early years," says Sacerdoti, "now among the top executives of the European Commission, who was still grateful because I had given him without any problems permission to do an exchange abroad with recognition of the related exam, which in those days was rather hard to obtain. But for me it was right that he did not miss this opportunity for an international education."

However, one cannot talk about Giorgio Sacerdoti without remembering his commitment to religious freedom and the protection of minorities. Sacerdoti was born into a Jewish family in 1943 amid extreme danger, and only by taking shelter in Switzerland did his parents and he, born only a few months before, escape Nazi-Fascist persecution. When in the mid-1980s Italy decided to replace the 1929 Concordat, abolishing the state religion and thus putting all faiths on an equal footing, Sacerdoti was the chairman of the Legal Commission that negotiated, along with the government for the Union of Jewish Communities, the accord governing the status of Judaism in Italy under Article 8 of the Constitution. He is currently head of the Contemporary Jewish Documentation Center in Milan, which is based at the Central Station where the Shoah Memorial is located, better known as Binario 21. "The commitment of Jews in defense of the values of freedom and equality is in the interest not only of themselves but of everyone," Sacerdoti says. This is shown in his 2021 volume published by Il Mulino Law and Judaism. Italy, Europe and Israel, which collects more than fifty of his writings on the subject, including articles in newspapers and scholarly essays.

The whole picture is not yet complete. Giorgio Sacerdoti's passion for the mountains is well-known, and not just as an ordinary hiker. Sacerdoti has made it to the top of the Matterhorn, Kilimanjaro and Ruwenzori, and has participated in ski-mountaineering expeditions to Patagonia and the Himalayas on skis even at an age when many climbers had already hung up their boots. When speaking of mountains, his face lights up: "The Matterhorn is not the highest mountain I have climbed. But it is perhaps the one that gave me the most satisfaction, because the climb is steep and unbroken, and you can never pause to rest." Sacerdoti approached the mountain, we are told, with the same commitment he has put (and still puts) into research, teaching and shaping young students.