Getting Rid of Zombies: How to Improve the Accounts of Italian Companies

Italian governments, from the beginning of the pandemic to December 2021, used €260bln to support corporate liquidity. According to a study by Bocconi University's Equita Research Lab in Capital Markets, presented yesterday, this expenditure has managed to limit bankruptcies, thus maintaining employment and production, but the greatest dangers are hidden in the phasing-out period, when the measures put in place for the emergency will be gradually withheld. Small and medium-sized enterprises are especially at risk, also in light of the negative developments due to the war in Ukraine.

The authors of the study (Stefano Caselli and Stefano Gatti, Bocconi University, Carlo Chiarella, CUNEF Universidad, and Marco Clerici, Francesco Asaro and Francesco Botti, Equita) observe that financial support has inevitably gone both to companies with a simple liquidity crisis and to those destined to disappear without public aid (the so-called zombie companies). Furthermore, the aid - essentially in the form of guaranteed financing - has affected a productive system that was already undercapitalized and over-leveraged.

The study defines zombie firms as those that are in at least one of the following two conditions:

- Report a negative return on assets (ROA), a negative percentage change in net fixed assets and an EBITDA to debt ratio below 5% over two consecutive years.

- Report an interest coverage ratio computed on the basis of EBITDA that is below 1 for two consecutive years.

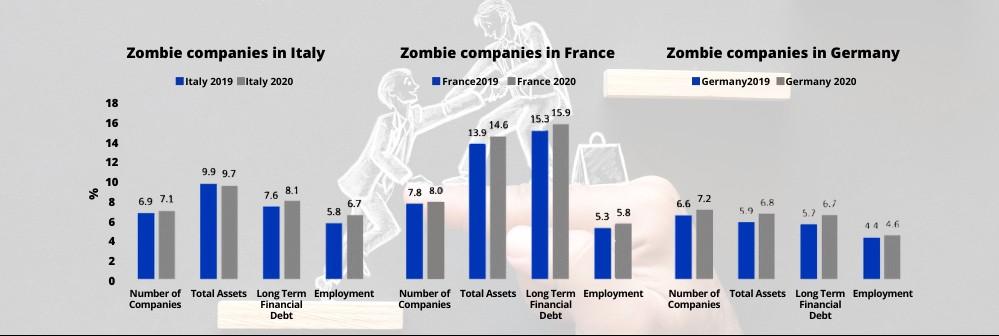

Following this definition, zombification affects all major European economies, with an incidence ranging from 7.1% of companies in Italy, 7.2% in Germany, up to 8% in France. However, the social risk is higher in Italy, where these companies account for 6.7% of employment, compared with 5.8% in France and 4.6% in Germany.

"While state-guaranteed loans have helped businesses avoid a liquidity crisis, European companies are facing historically high debt levels, deteriorating profitability and undercapitalization, which is a bad combination for solvency in the medium run," says Stefano Gatti.

Regarding the undercapitalization of the Italian system, the authors calculate that the capital injection needed to bring all companies to an investment grade rating (BBB-) is €532bln (74 attributable to zombie companies). Even to reach a more modest B- rating, €188bln would be needed (37 for zombie companies).

The study closes with a strong policy recommendation, dictated by banks' heavy exposure to the guaranteed debt of small and medium-sized enterprises. "If, in the coming months, firms are unable to repay," Professor Gatti says, "banks have no incentive to restructure their debt and, indeed, a strong incentive to cash in on government guarantees, thus sealing the fate of those firms."

Scholars suggest, then, that specialized operators (servicers), equipped with instruments to proactively manage credits backed by public guarantee, set up special vehicles designed to purchase guaranteed credits from banks, paying them with senior notes (for the guaranteed part) and junior notes (for a fraction of the excess).

In the case of a guarantee on 80% of the debt, for example, 80% could be paid with senior notes (the safest) and 5% with junior notes. In this case, the banks would have an incentive to sell the credit, with the prospect of recover more than the guaranteed amount, and the servicers would have every interest in proactively managing the debt of the companies, in order to put them in a position to repay an even greater portion, which they would collect.