Deposit Insurance and Bank Runs in Reverse

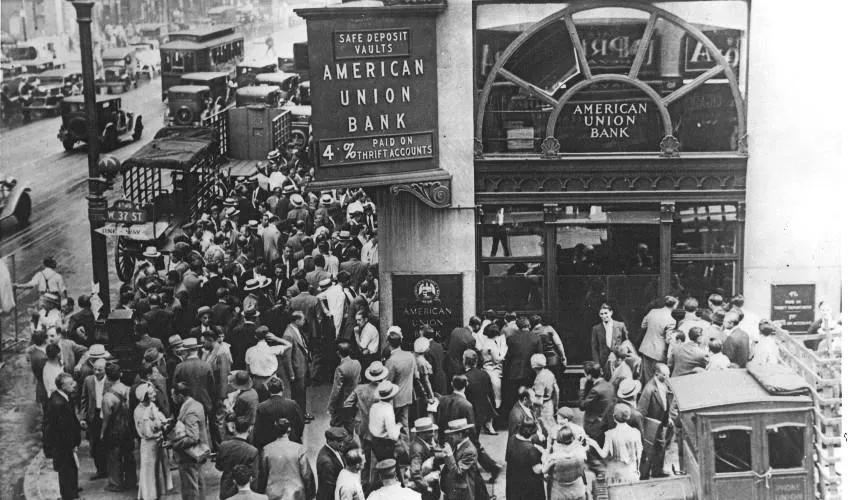

One of the feats that earned Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig the 2022 Nobel Prize in Economics (joint with Ben Bernanke) is a model of bank runs and related financial crises. In an article published in 1983, they noted that, in 1930s America, people would cash in their savings as soon as rumors about a bank's financial health started to spread, lest the bank go bust and they lose their money. Such bank runs, though, were the reason why many, otherwise healthy banks collapsed in those years. Government-guaranteed deposit insurance, the Nobel laureates concluded, is the best solution to this problem.

Nicola Limodio (Bocconi Department of Finance), in a forthcoming paper with Nicolás De Roux (University of the Andes), found that deposit insurance motivates people to keep deposits immediately below the insured threshold ("bunching" behavior) and that an increase in the insured amount leads savers, and especially bunchers, to change their asset allocation and to increase their deposits. The authors were able to estimate the elasticity of deposits to insurance: in their case, a 1% increase in the share of insured deposits translates into 2.3% additional deposits.

The effect of changes in deposit insurance on depositor behavior is difficult to observe because the threshold is usually increased in case of financial crisis, when the effect of the policy change cannot be disentangled from the effects of other economic forces. In times of financial distress, individuals may change their deposit behavior for reasons unrelated to changes in the insurance threshold.

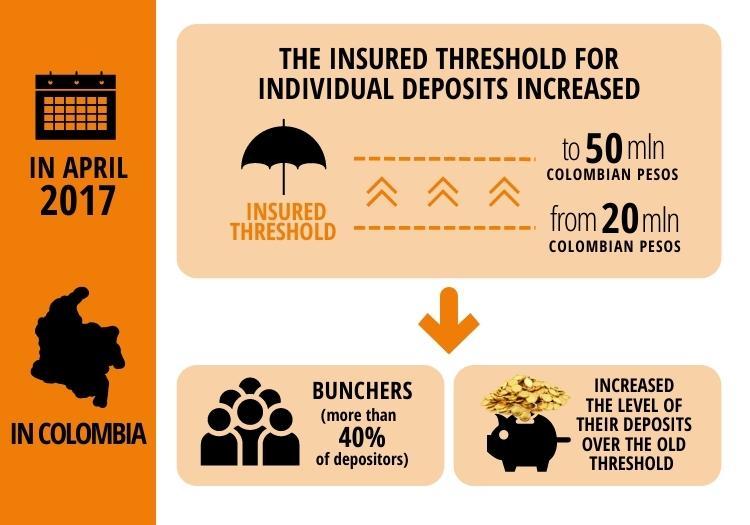

Infographic by Weiwei Chen

In April 2017, though, the Colombian deposit guarantee fund increased the insurance for individual deposits from 20mln Colombian pesos (COP) (approximately 6,780 USD) to 50mln COP (around 16,950 USD). The change was unexpected and motivated only by the need to update the real value of the insurance threshold, which had not changed since the year 2000.

"We partnered with a large bank in Colombia and obtained two years of monthly records of individual deposit holdings for more than 50,000 individuals," Professor Limodio said. "We observed that more than 40% of savers exhibited a bunching behavior and that they increased the level of their deposits after the threshold change much more than those with already higher deposits."

The driver of this effect was the increase in the expected return of deposits that induced individuals to substitute other assets to increase savings.

"Deposit insurance is an effective form of regulation," Prof. Limodio commented, "but it creates costs, since it encourages the moral hazard behavior of banks and increases the risk-taking of the financial system as a whole. These costs and benefits should be weighted to determine the optimal level of deposit insurance. Therefore, understanding the channels through which the insurance encourages deposits and estimating its causal effect on depositor behavior is critical."

Nicolás De Roux, Nicola Limodio, "Deposit Insurance and Deposit Behavior: Evidence from Colombia." Forthcoming in Review of Financial Studies. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhac092.